A Visit to the Lynching Legacy Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama (August 2019)

In his book Tears We Cannot Stop: A Sermon to White America,

Michael Eric Dyson includes a list of things majority culture people

can do to understand the obdurate presence of racism in our national

life. “Beloved, you must also educate yourself about black life and

culture. Racial literacy is as necessary as it is undervalued.”

Last

summer, from May to August, while in the grips of a dysphasia that

caused me to lose 43 pounds (unintentionally), I did just that—educate

myself. The New Jim Crow is on my dedicated bookshelf space, as is White Fragility, The Cross and the Lynching Tree, White Awake, The Color of Water, Whistling Vivaldi, Blindspot and Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? None of these, as far as I can tell, are included in Dyson’s list of must-reads, his starting with James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time.

Though

this pile of mine is daunting reading, I realized when comparing my

list of titles to Pastor Dysons’s suggestions that I have hardly

started in this self-appointed journey of becoming racially literate. I

too want to repeat the phrase so familiar these days, Well, I’m not racist. However, my recent plunge into the topic has convinced me that the concept of a recovering racist describes myself more accurately.

All

this despite the fact that in the later part of the 1960s, David and I

were part of a small cadre of evangelicals who committed themselves to

attempting to do something about the racial divide in American

churches. We planted a church on Chicago’s west side with an

intentional commitment to build an interracial staff and an interracial

congregation. This racism despite the fact that for six years in the

1990s, we were the only whites who attended an all-black congregation.

You

see, white privilege is the milieu into which I was birthed, a status

of life granted extravagantly, not earned; absolutely taken for

granted; and rarely, until this last decade, widely examined. It is a

condition of being I have only lately started to gaze at in the mirror

of my existence, guided by the articulate and sometimes not-so-gentle

explanations of the authors of the books mentioned above.

So

until those of us who are members of this societal strata begin to

really examine the privileges of whiteness and struggle to understand

how that privilege actually inhibits the full development of other

races through conscious or unconscious systemic prohibitions, which

inevitably displays itself in culture as a racist status-quo—we cannot make significant progress. So, I

have ordered Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped From the Beginning, his history of racist ideas and winner of the National Book Award and also his new book How to Be an Antiracist.

I may be a recovering racist, but at least I am determined to be an educated one.

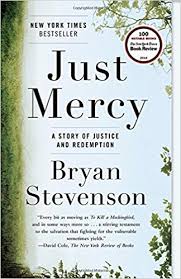

In all of this, last summer (at about the negative weight loss of 23 pounds), I plunged into Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption

and discovered the voice of a true American leader. As a young

attorney, Stevenson founded the Equal Justice Initiative, established

as a legal practice dedicated to “defending the poor, the wrongly

condemned, and those trapped into the furthest reaches of our criminal

justice system. One of his first cases was that of Walter McMillan, a

young man sentenced to die for a notorious murder he didn’t commit.

This case opened for Stevenson a tangle of conspiracy, political

machination and legal brinkmanship.” (back-cover copy)

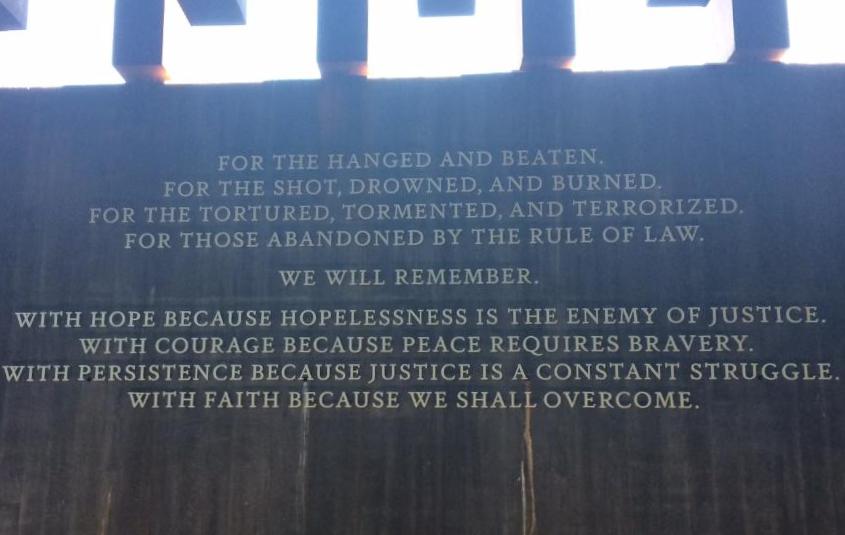

The

EJI was responsible for conceiving of and erecting the Lynching

Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama, which opened last year when I hit

negative weight loss of about 30 pounds. It is a “comprehensive

memorial dedicated to racial terror lynchings of African Americans and

the legacy of slavery and racial inequality in America.” The Clarion Journal, writing about the opening of the memorial, uses stark language to describe its impact:

Visitors

to the new National Memorial for Peace and Justice first glimpse them,

eerily, in the distance: Brown rectangular slabs, 800 in all, inscribed

with the names of more than 4,000 souls who lost their lives in

lynchings between 1877 and 1950.

Each pillar is 6 feet (2

meters) tall, the height of a person, and made of steel that weathers

to different shades of brown. Viewers enter at eye level with the

monuments, allowing a view of victims' names and the date and place of

their slaying.

As visitors descend downward on a slanted

wooden plank floor, the slabs seemingly rise above them, suspended in

the air in long corridors, evoking the image of rows of hanging brown

bodies.

I was determined to go, to drive the 13

hours and be one of the white Americans honoring the goal of

resurrecting a gruesome national history heretofore relegated mostly to

sidebars and short articles in schoolbooks and dusty stacks in library archives.

Instead, wiser heads prevailed (I also missed my grandson’s wedding),

and David and I fit that journey to Montgomery this August of 2019.

There

aren’t many “sacred” places left in the world. Even our cathedrals are

often full of shuffling tourists. Church doors are mostly locked during

the week. Sometimes we feel awe—at the Grand Canyon, for instance, or

at the seemingly endless sweep of a prairie or at acres of land waving

with growing wheat. We are rarely hit with the impact of a physical

monument, however, with the kind of power that makes you want to fall to

your knees, raise your hands and say, “Surely the Lord is in this pace.”

Better

yet, rare is the fall-flat-on-your face in the ancient posture of being

undone before something greater than you can comprehend.

The

Lynching Memorial has signs on the walls: “This is a sacred space,” and

asks visitors to act accordingly. Richard Jones in the Winston-Salem

Journal attempts to describe it all: “Inside the open-air structure,

visitors walk among the hanging steel coffin-sized monuments—one for

each county in which a lynching took place—silently or speaking in

hushed tones. … Between 1877–1950, 4,000 Americans were lynched, mostly

but not exclusively in the South, taken from their homes or jails where

they were awaiting trial as accorded by the Fifth Amendment to the

Constitutions and ‘swung from the limb of a tree,’ as a North Carolina

newspaper put it. That’s an average of one lynching each week for 3

years.”

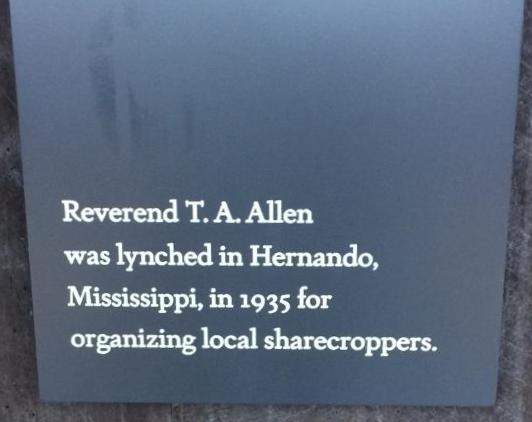

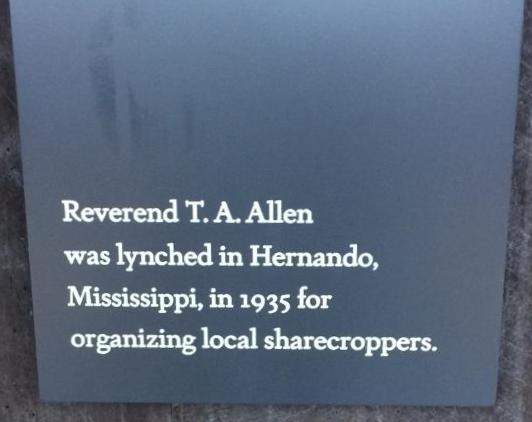

Plaques on the wall (as the wooden walkway descends

deeper into the Memorial and the bronze coffins now hang above your

head) commemorate individual acts of horror, such as these:

David

Walker, his wife, and their four children were lynched in Hickman,

Kentucky in 1908 after Mr. Walker was accused of using inappropriate

language with a white woman.

A lynch mob of more than 1,000 men, women and children burned Zachariah Walker alive in Coatsville, Pennsylvania, in 1911.

Mary

Turner was lynched with her unborn child, at Folsom Bridge at the

Brooks County Line in Georgia in 1918 for complaining about the recent

lynching of her husband, Hayes Turner.

At least, the dirge I sing, I am a racist recovering, is no longer a solo soliloquy. There are others bowing their heads in a dirge of horror. To quote Richard Groves again:

A

young Muslim mother said in an interview after 9/11 that on seeing the

planes explode into the World Trade Center her unpremeditated prayer

was, “Dear God, don’t let them be Muslim.” She feared other Americans

would generalize their feelings about the ones who flew the planes to

all Muslims, to her and her family.

When

I heard that a gunman had shot his way into the newsroom of the Capital

Gazette and killed five people, I did not pray, ‘Dear God, don’t let

him be white,’ even though most mass shooters are white. I knew that no

one would think that his murderous impulses, whatever they were, were

somehow connected to the pigmentation of his skin. His atrocity had

nothing to do with me as a white man.

Yet when I stood

beneath the hanging steel monuments—“strange fruit” indeed—in the

lynching memorial, and when I stood wordlessly beside other visitors,

most of whom were African-Americans, before a display of more than 200

jars containing dirt from an equal number of lynching sites, each jar

bearing the name of a black man who was lynched there, I felt white.

And I was ashamed.

Ta-Nehisi Coates used his book Between the World and Me

to pen a letter to his son about growing up Black in a

white-power-structure world. The father recapitulates American history

and explains how “racist violence has been woven into American

culture.” Coates sees white supremacy as an indestructible force, one

that Black Americans will never evade or erase but will always struggle

against.

I am no prophet and I hope the author is wrong, but

with some sort of foreboding premonition, I suspect he is right.

Yet—yet, because I am part of the white culture, I dare to hope,

arrogant as this might seem to others, naïve due to my lack of personal

suffering due to the permanence and evil of systemic racism, due to the

fact that I am essentially and indubitably Christian and therefore, not

only on the one hand skeptical due to evil’s horrific hold on the heart

of humans, but still consistently hope-filled—I pray that he is wrong.

I

would like, personally, to advance from this state of being a recovered

racist to that of being a mostly recovered racist. At the least, I want

to become someone who is not ignorant about the racial horror embedded

in the genetic DNA of our country’s culture. I do not want to defend it

or explain it away. I do not want to burrow into a self-protective

cocoon because nothing (except my own conscience) demands that I

intentionally inform myself to the cries of my culture. Instead, I vow

to expose myself and my mentality to the humiliations and terrors and

violations that others have suffered essentially because their skin is

a different color from my own.

Robin DiAngelo writes in her book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism,

“The very real consequences of breaking white solidarity play a

fundamental role in maintaining white supremacy. We do indeed risk

censure and other penalties from our fellow whites. We might be accused

of being politically correct or might be perceived as angry, humorless,

combative, and not suited to go far in an organization. In my own life,

these penalties have worked as a form of social coercion. Seeking to

avoid conflict and wanting to be liked, I have chosen silence all too

often.”

My Scripture reading for this morning was from that seminal chapter in Isaiah, chapter 58, verses 9-11:

“If you do away with the yoke of oppression,

with the pointing finger and malicious talk,

and if you spend yourself in behalf of the hungry

and satisfy the needs of the oppressed,

then your light will rise in the darkness

your night will become like noonday.

The Lord will guide you always,

He will satisfy your needs in a sun-scorched land

And will strengthen your frame.”

If

we take this Scripture as a universal promise rather than an individual

one, how can we—a corporate, breathing entity of people who want to

change the present but must do so only with a recognition of the

past—not clutch tightly to hope? I, for instance, will give myself to

learning how to “satisfy the needs of the oppressed.” I will, at the

least, attempt to hear their voices and learn to listen to their

stories.

I may be a recovering racist, but at least I am becoming an educated one.

Karen Mains

NOTICESI Bid Your Prayers

In

some of the churches we have attended, the pastor or a deacon often

calls the people to prayer by saying, “I bid your prayers for

___________. Then, the congregants fill in the blanks.

So,

in these notices, I bid your prayers for my writing. (You can fill it

in with your own words.) Through the 18 years that I have been working

with Hungry Souls, I and teams of people working alongside me, have

accumulated well-tested spiritual-growth ideas that have been designed

in multiple of tools—all of which need to be published and made

available to other would be users.

So instead of

conceptualizing other ideas, I feel the need to finish all this work

while I still have time. Believe me, this is a labor of love. And even

though it is a loving project, it still entails all kinds of hours,

days and months in front of a computer screen.

So I bid your prayers for ___________________. You can fill in the blank.

I

also feel called to write out into general culture, into those secular

markets that don’t have a clue as to who Karen Mains is and who will

have to prove to them that she does have writerly capabilities.

Consequently, I spent a lot of last month pulling together a cover

package to sell my writing potential to New York literary agencies in

order that I might have someone to present my articles, book proposals,

etc. to secular publishing houses.

It has been a daunting

task, to say the least. One cover letter written, edited and designed.

One brief bibliography of the books I’ve written in religious markets (23 at last count).

One query letter; mine is titled “Beware Little White-Haired Ladies.”

One book proposal (Uncommon Goodness:

How Renegade Leaders Create Virtuous Circles That Defeat Vicious Cycles

of Poverty, Ignorance, Disease and Despair). One sample

chapter, and since this book is about the “renegade” leaders who do

good in the world, one profile of real people who challenge the ills of the world—the only piece in this puzzle that has

still to be created.

No wonder I am mentally exhausted! From

the past of dim memory, I recall some writer friend saying that pulling

all the above stuff together is about as much work as writing the book

itself. That vague statement has been some comfort.

Once

that short profile is written, I have several articles ready to adapt

and send out to secular periodicals! My goal is to submit 50 (fifty?!) articles by the end of this year.

I will never run out of ideas, but I will run out of stamina. I bid your prayers. Reminder!

The Soulish Food e-mails are

being

posted biweekly on the Hungry Souls Web

site. Newcomers can look that over and decide if they want to

register on the Web site to receive the biweekly newsletter. You might

want to recommend this to friends also. They can go to www.HungrySouls.org.

Hungry Souls Contact InformationADDRESS: 29W377 Hawthorne Lane

West Chicago, IL 60185

PHONE: 630-293-4500

EMAIL: karen@hungrysouls.org

|

|

Karen Mains

I vow to expose myself

and my mentality to the humiliations and terrors and violations that

others have suffered essentially because their skin is a different

color from my own.

BOOK CORNER

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption

by Bryan Stevenson

After reading this book, I thought to myself, This man, certainly, is one of the rising leaders of our country. Thank God.

Bryan

Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, tells that

story in this book. The back-cover copy touts the man’s credits: “From

one of the most brilliant and influential lawyers of our time comes an

unforgettable true story about the redeeming potential of mercy.”

Of

course, a reader expects such praise from book-cover copy; it’s written

by staff in whatever house has published the book. What one doesn’t expect are the outside accolades. These can’t be manufactured by editors. After that most coveted of prizes “#1 New York Times Bestseller,” the list reads as such:

“Named one of the best books of the year by The New York Times • The Washington Post • The Boston Globe • Time • The Seattle Times • Esquire.

Then—“winner of the Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Nonfiction; winner

of the NAACP Image Award for Nonfiction; winner of the Books for a

Better Life Award; finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize; finalist for the Kirkus Prize, and an American Library Association Notable Book.”

These

kudos alone would make most wannabe readers at least pick up the book

and browse the pages. I guarantee, however, that pure goodness radiates

through the reading, and, indeed, mercy is restored as an admirable and

desired trait for much of what ails our often bitter and heartless

society.

In the powerful book Lynching in America,

which David and I picked up in the bookstore of the Lynching Memorial,

compiled and written by the EJI staff, James Stevenson is mentioned

once, and a photo of him with the EJI staff highlights the monumental

work they did for the memorial. He remains nameless.

The man, obviously, is not one of the “hot shots” among the rising leaders of our times.

Get the book. Read it.

|